I was the co founder of Intel Capital and Vice President of Business Development at Intel. I left in 1999 to advise companies, sit on corporate boards and invest in early stage companies for my own account. While many considered me as a venture capitalist (for instance I was listed as number eight in the Forbes Midas List in 2003), I never thought of myself that way. At Intel, I saw early stage investing as a tool for achieving strategy. That is why I referred to myself as an activist strategist. But in my role at Intel, I worked closely with venture capitalist and as well as with founders. But I did not identify with either. I never started a company because I considered that too risky. While I had many significant opportunities to join venture capital and private equity firms as a partner, I knew I would not feel comfortable in that role. But all this experience has given me a perspective on the inherent conflict between founders and venture capitalist which I am sharing here.

Venture capitalists (VCs) and founders are often not aligned—but it’s the VC’s job to convince them that they are.

VCs pitch themselves as more than just capital. They say things like, “We’re not just money—we’re partners on your journey.” They’ll list all the ways they can help the startup succeed. And indeed, a good venture firm can add significant value.

But what they won’t do is explain the fundamental conflict: VCs and founders define success differently. For founders, success means building a successful company and creating personal wealth. For venture funds, success means generating returns for the fund and making themselves rich in the process. These are not the same thing.

In fact, with the unlikely outcome of a major liquidity event, the next best thing that can happen to a founder is an early failure. I’ll explain why.

How Venture Capitalists Make Money

Venture capitalists invest in portfolios—usually 20 to 50 companies per fund. This diversification is key to their success. Founders by contrast, are all-in on one company. That’s where the conflict starts.

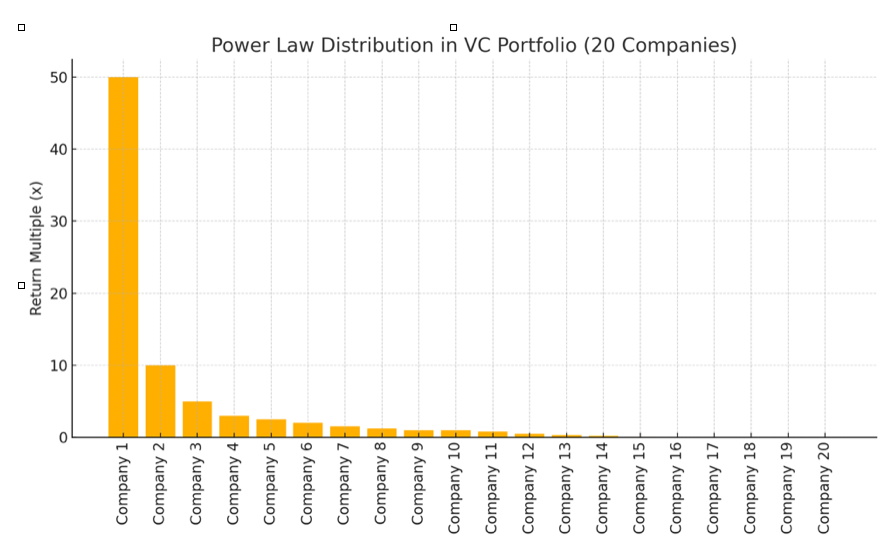

VC returns are driven by what’s known as a power law distribution—just a few companies return the majority of the fund’s profits.

Here’s a simplified example:

• Total invested: $20M

• Total return: $79.1M

• Fund multiple: ~4x

VCs earn a 2% annual management fee and a 20% carried interest (the share of profits). Top-tier funds sometimes negotiate even better terms. Most of their focus is on expected return: a weighted average of all outcomes. VCs typically target a 10x return per investment, knowing full well that only one or two companies will achieve it.

A typical portfolio might look like this:

• 70% fail (return $0)

• 20% return $1–3M

• 7% return $10–40M

• 3% return $100M+

From the Founder’s Perspective

Let’s consider a founder’s odds:

• 70% chance of failure

• 20% chance of a small or break-even outcome

• 10% chance of a meaningful return

And remember—VCs usually hold preferred stock while founders and employees hold common stock. So even if a company is sold for a modest return, VCs might recover their investment while the team walks away with little or nothing.

Realistically, founders have about a 1 in 10 shot at a significant payday—and some studies suggest it’s closer to 2%. Even if there is a successful exit, it can take 7–10 years. Many founders work for a decade and end up with little or nothing.

Not All VC Firms Are Successful

VC fund returns also follow a power law. Fewer than 20% of VC firms deliver strong returns for their limited partners. That further reduces the odds for founders, depending on which firm they partner with.

Success among VC firms is not about having more winners, but about having bigger ones. Being backed by a top-tier firm may increase expected value, but it doesn’t improve the founder’s probability of a meaningful payoff.

Diverging Interests

Here’s the real divergence: VCs are playing a portfolio game. They’re often willing to increase the risk of failure for a company if doing so raises the fund’s expected return.

For example:

Scenario 1:

• 50% chance of $10M exit

• 50% chance of failure

→ Expected value: $5M

Scenario 2:

• 20% chance of $50M exit

• 80% chance of failure

→ Expected value: $10M

The expected value doubles, so the VC favors the riskier path. But the founder may not—because they only get paid if the company survives.

I recall a startup where two founders each held 25% of the equity. A VC owned 40%, and I held part of the remaining 10%. The company was doing well. I found a buyer willing to pay $160 million. That would have meant $40 million for each founder—not bad for two guys in their twenties.

But the VC thought the company could be worth $1 billion and persuaded the founders not to sell. I urged them to take the deal and use their proceeds to fund another startup. They declined. The year was 1999. The internet bubble burst shortly after, and the company was wiped out.

Are Founders Irrational?

Some founders don’t fully grasp the financial structure of venture capital. Others do, but believe they’ll beat the odds due to their brilliance and vision. It’s not unlike roulette.

Over my career, I’ve invested in over 20 startups, including a few successful ones like Pluto TV, Oura Ring, and Neutrino. I’ve had five complete failures and five companies still in flux. I’ve never wanted to be a founder myself—but I’m grateful that others are willing to take that leap.

The nature of venture capital means wealth often flows from founders to investors. It’s not that VCs don’t want success—they do. But they also understand how random outcomes can be. As I often say: luck is the strongest determinant of success, and the greatest mistake is confusing luck with being smart.

What About Limited Partners?

Limited Partners (LPs)—the investors in VC funds—are usually institutions like pension funds or insurance companies. Fewer than 20% of LP dollars come from high-net-worth individuals. LPs are aligned with VCs, not with founders.

I’ve been an LP in several VC funds, sometimes on favorable terms in exchange for guidance—and I’ve done very well.

And Then There Are Angel Investors

Angel investors fall into two broad categories:

1. Professional Angels: Wealthy individuals with early-stage experience and strong networks. They behave like mini-VCs, investing early with high risk and occasional high return. Deep pockets are needed, especially to survive recapitalizations (or ‘cram-downs’).

2. Friends and Family: Typically lack both capital and diversification. They often suffer the same fate—or worse—than the founder they back.

Final Thoughts

The disconnect between founders and venture capitalists is structural, not personal. It’s portfolio math versus personal risk.

Founders bet everything and mostly end up with nothing. VCs spread their bets and may win big. While They need each other—but don’t be fooled into thinking they’re on the same page.