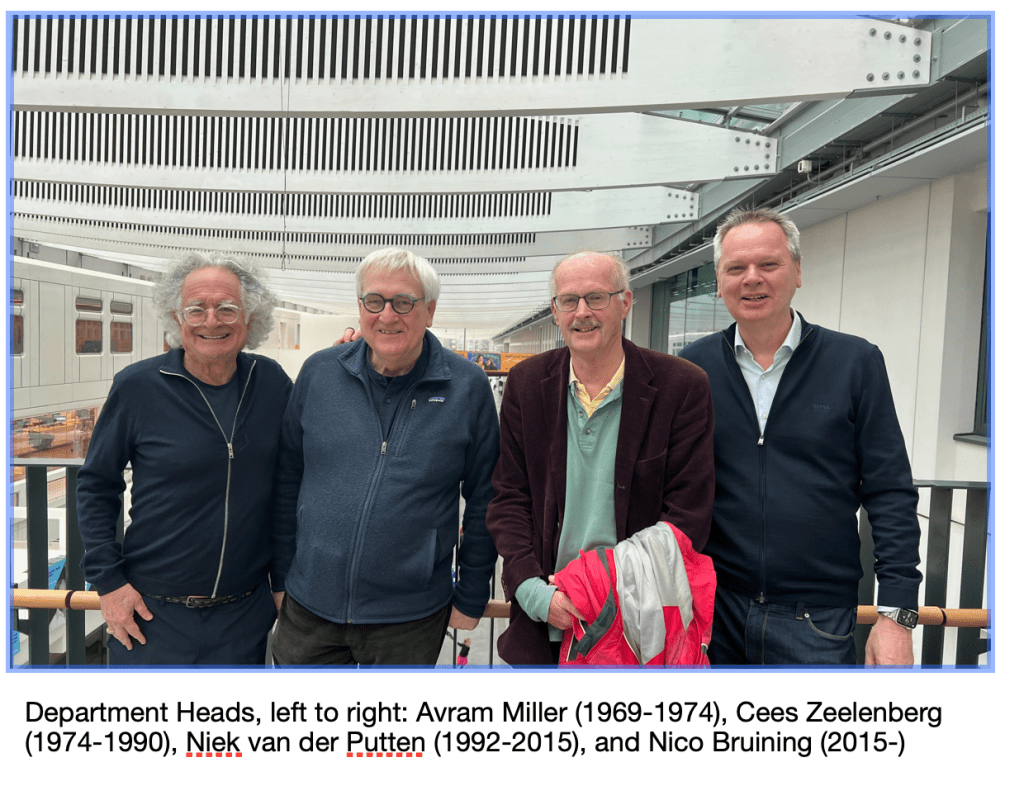

Fifty-five years ago, I moved from San Francisco to Rotterdam to join the staff of the Thoraxcenter, which became one of the world’s leading heart centers. It has been 50 years since I was last there. Nico Bruining, the current occupant of my previous position as head of the computer department, kindly invited me to visit. He surprised me by inviting two other former heads to join us. Together, we represented four generations.

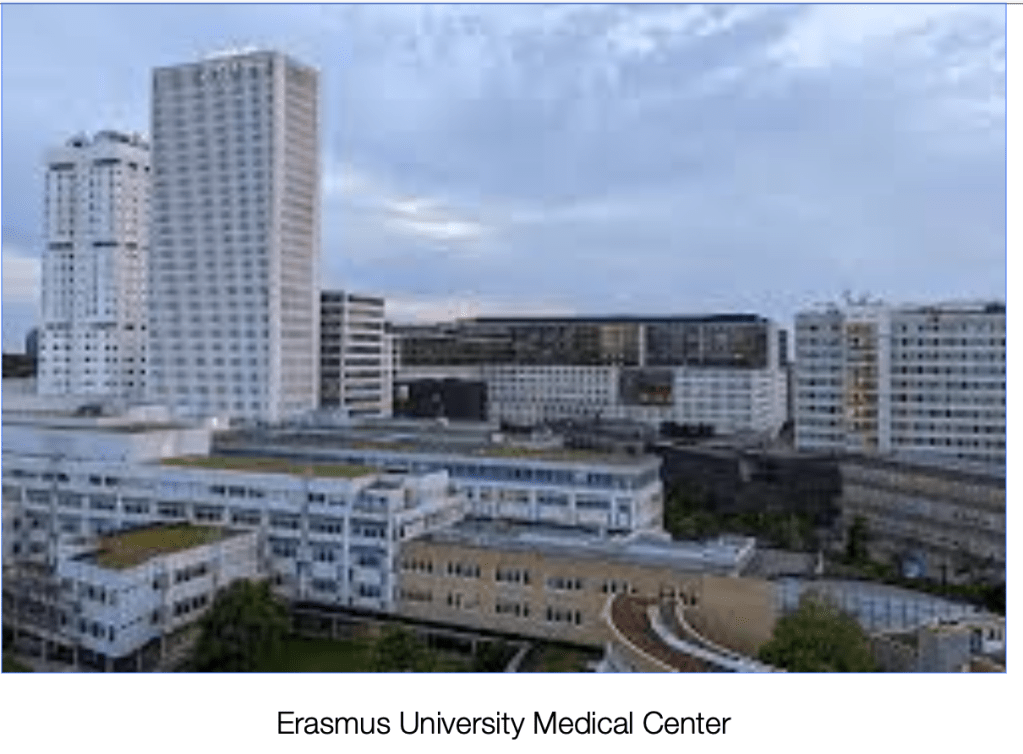

The Thoraxcenter had been housed in a separate four-story building. My office was on the third floor, and I looked out at a beautiful park. Now, that building is mostly empty and will be used for other purposes. We toured the facilities, but entering the area where my group was formerly located took was not possible. That was a disappointment. I wanted to be in the computer room, where I had experienced so much joy.

The Thoraxcenter is now integrated into the massive Erasmus University Medical Center. With 1,200 beds and more than a million outpatients treated annually, it is the largest medical facility in the Netherlands. Although the current facility was completed in 2018, its origins go back to 1966, when the Medical Facility of Rotterdam was first established.

I joined the Thoraxcenter in April 1969 at the age of 24 and left in 1974. There I established and led the Department of Clinical and Experimental Information Processing Department, known in Dutch as the Afdeling Klinische en Experimentele Informatieverwerking (AKEI), reporting to Professor Paul Hugenholtz, the Thoraxcenter’s visionary founder. When I left, my title was Hoofd Medische Werker, equivalent to department head.

Those five years at the Thoraxcenter were some of the most impactful years of my life, professionally and personally. I transitioned from an individual contributor to a manager and from a technician to a scientist.

Reflecting on Computers in 1970

I want to reflect on the capabilities of computers in 1970. Even though I have fortunate to have experienced the development of computers for more than half a century, I can barely comprehend the changes that have taken place and can scarcely imagine what is to come.

The main computer we used, a PDP-9 manufactured by Digital Equipment Corporation, was called a Minicomputer even though it weighed 350 Kilograms. To give you an idea of its computing capabilities, my electric toothbrush is significantly more powerful than the PDP-9. A single photo on my iPhone is 30 times larger than the PDP-9’s main memory. In fact, the iPhone in my pocket is more powerful than all the computers that existed in the world in 1970.

Meeting with my successors

The four of us reminisced. We discussed the past and the evolution of the Thoraxcenter. We also discussed the many people who were part of the founding team and stayed on. Sadly, many, if not most, have passed on.

I was surprised to learn that no computers are physically located on the premises; all the computers are now off-site and connected by high-speed networks. I also learned that starting in 1993, the Government of the Netherlands began regulating medical devices and computer systems. The Thoraxcenter could no longer use the systems that had been developed there and was forced to transition to transition to commercial systems. When I was there, it was the Wild West of regulations; there were none. We could build systems, and if we thought they worked, we deployed them.

Paul Hugenholtz Vision

Working in Boston, the leading area in the world at that time for computer technology, he began to understand the potential of computers to play a role in medical science and patient care.

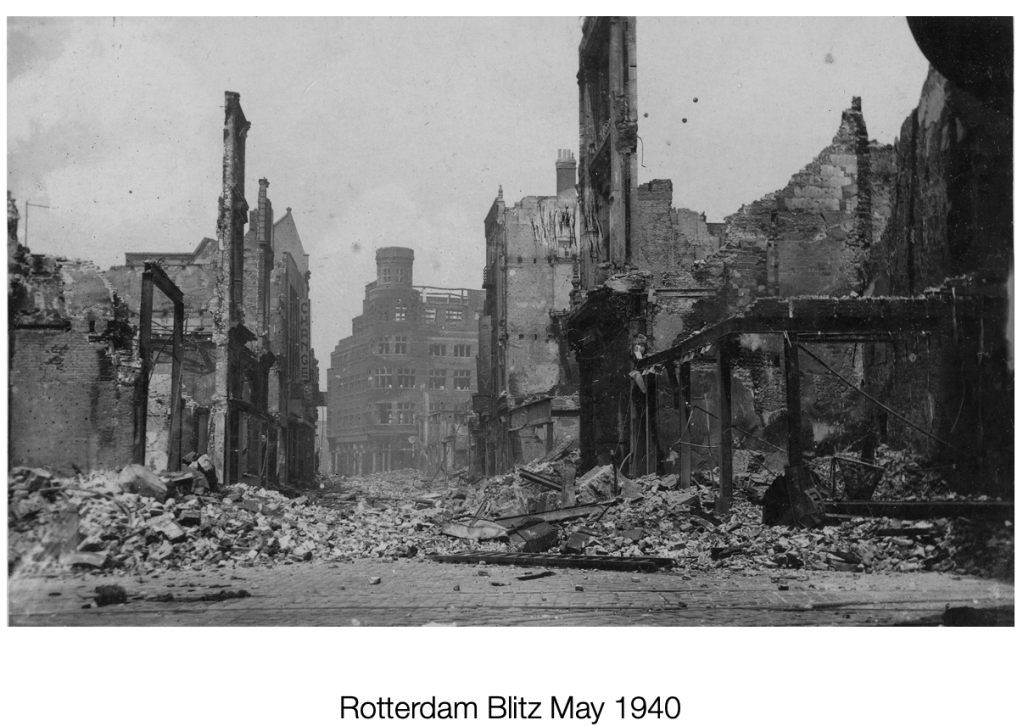

Rotterdam was heavily damaged during World War II. The city suffered extensive destruction on May 14, 1940, when the German Luftwaffe bombed it. It still showed signs of damage when I moved there in 1969. The government of the Netherlands decided to make significant investments in the reconstruction (Wederopbouw plan) of Rotterdam. These involved creating a medical school along with a university hospital. It had been decided to start by creating a center of excellence for cardiovascular and pulmonary medicine, which would be named Thoraxcenter. It would become one of the first heart hospitals in Europe. But to make it happen, a visionary leader had to be found. In 1968, Paul Hugenholtz was identified to be this leader.

At first, Paul was not interested in leaving Boston, but starting something with the magnitude of the Thoraxcenter was very appealing. The new center would inherit a four-story building built as a test run for the School of Medicine building, which would be 31 stories high. The Dutch government had allocated many million dollars to develop the Thoraxcenter, which was fantastic. In addition, he got Philips, a leading Dutch conglomerate with a significant medical business, to provide a lot of funding. Under the leadership of Hendrik Casimir, the head of their R&D, Philips would provide the funding that enabled the Thoraxcenter to bring me to the Netherlands.

Paul grasped the potential of computers for patient care. He wanted to develop a computer system to monitor patients in the intensive care unit and use computers for diagnostic purposes, notably to support the catheterization lab. He was early to recognize the importance of Echocardiology and recruited Kaas Bom, a young engineer working with the Dutch Navy on using ultrasound for submarines. Paul realized the importance of biomedical engineering, as he knew his vision would require creating new medical devices.

In 1968, Paul embraced the opportunity to create the Thoraxcenter. His partner was the famous Dutch cardiac surgeon Jan Nauta. Paul needed someone responsible for technology, which initially included medical devices and computers. He recruited a biomedical engineer named Jerry Russel, who was then leading the biomedical department at an academic hospital in San Francisco. Jerry, who had a limited understanding of computer technology, sought people to join him at the Thoraxcenter. One of my friends at the time had worked for him and told Jerry about me. Jerry had already moved to Rotterdam. Both Paul and Jerry contacted me and encouraged me to leave my position at the University of California Medical School, where I worked as a research assistant, to join them in Rotterdam to create the Thoraxcenter. While I was reluctant to leave, the opportunity to build something on the scale of the computer department at the Thoraxcenter was captivating. Moving back to Europe also was a strong draw. I had lived in Paris and London in 1965/66.

A wild duck flies to the Netherlands

Those who read my blog know I have a rather unusual background. I am self-educated (I tested out of high school and never went to University). My book, the Flight of a Wild Duck, covers how I became a technologist, medical scientist, corporate executive, and venture capitalist. I joined Professor Joe Kamiya in 1966. He pioneered brain wave bio-feedback, and I had a deep understanding of hardware and software. I started programming computers in 1967. I had a talent for electronics and, primarily, digital technology, although I could also build analog devices. I was the ultimate full-stack developer who could create digital logic from transistors, resistors, and capacitors, design computer architecture, and do advanced programming.

Avram’s lecture at the Dutch Computer Society 1970

The equipment I developed for bio-feedback of brain waves (the first of its kind) requires real-time analysis. I like to joke that I was the leading expert on real-time physiological signal processing, but it might be true because I may have been the only one doing this then. We see this in devices like the Apple Watch and the Oura Ring. This capability intrigued Paul and Jerry because Paul wanted to develop a real-time patient monitoring system for the intensive care unit.

Towards the end of 1968, I began getting calls from Hugenholtz asking me to move to Rotterdam and join his team. He was charming and persuasive. However, the major attraction for me was the budget for the computer development and the opportunity to build something at scale. I realized there was more money in hearts than brains. Paul would call me early in the morning, waking me up. Eventually, I said yes. Paul was one of the most persuasive people I have ever known. Before joining Professor Kamiya, I was the manager of a pizza restaurant and, before that, a Merchant Seaman. I played jazz piano and was active in civil rights and anti-war movements. These differed from the usual credentials for a technologist and scientist but did not concern them.

Arrival in Rotterdam

I arrived mid-day in Rotterdam, having stopped for a few days in London to see family. The first person I met was Arianne. She was Paul’s assistant, showed me around, and helped me get settled. We fell in love almost immediately. We were engaged three weeks after my arrival and married seven weeks later. Our first child, Adin, was born the following year, and our second son, Asher, would follow a few years later.

Then, I meet Jerry in person for the first time. I had already met Paul in his home in the Boston Suburbs, where his family was still living. I stayed at his house while taking a class at Digital Equipment Corporation and got to know the family.

Promoted

The relationship between Paul and Jerry was not working out. Furthermore, Jerry provided no added value to the computer activities. Soon, Paul put me in charge of the computer department and had me report directly to him. John Laird, a distinguished biomedical engineer from the USA, eventually replaced Jerry.

My department would eventually grow to over twenty people. I was 24 years old and had no managerial experience. Even though he did not understand the work of a computer department, Paul would guide me. While he knew little about computers, he understood people. He gave me confidence and insight into how to be a leader. It was challenging to get time with Paul. He was very busy and always traveling. So if I learned he was driving somewhere to have a meeting, I would show up next to his car and ask if I could ride with him. For instance, if he traveled to Amsterdam, I would get a few hours of his time. It was invaluable.

Putting the team together

Two people were already hired for the computer activities when I arrived: Cees Zeelenberg, who would eventually succeed me, and a man named Bruin, who became the first person I ever fired; I cried when I did that, and Paul told me it would get easier. I am afraid he was right. Cees, on the other hand, was a keeper. He was finishing his engineering degree at Delft University.

My first challenge was putting together the team. I brought Pete Harris over from Langley Porter. Pete was a bit younger than me. We had worked together programming the PDP-7 that the department had acquired. Pete was a very talented programmer and a lot of fun. He stayed at most of a year. I even brought over an assistant from San Francisco. She turned out to be a problem. She had been an ex-marine. One night, I was called by the police to pick her up after she was arrested for a fight in a gay bar. I had to send her back to the USA. Fortunately, I found a new assistant, Maud van Nierop. She was a talented and influential member of my team. Maud stayed at the Thoraxcenter until she retired about ten years ago.

At that time, few computer programmers were available in the Netherlands, so I recruited several from the UK. We were getting hardware support from a group that was part of the Dijkzigt Hospital, which later merged with the Erasmus Medical Center. That is where I met Wim Engelse. He was a technician there. He joined my team and, together with Cees, provided the group’s foundation. I loved working with them. It was an absolute joy. Wim would later join me at Digital Equipment Corp. While he, like me, never went to university, he was recognized for his technical capabilities at Digital. Wim later started a successful company. Cees went on to join TNO, an important research organization in the Netherlands, where he led their bio-medical activities.

The Patient Monitoring System

Jerry made the initial decision on the computer configuration. He decided to use two PDP-9s from Digital Equipment Corp. One was for the patient monitoring system, and the other was for programming and could serve as a backup. When I arrived, they were in the computer room but wrapped in plastic.

For most of those reading this post, it will be hard to imagine a time before personal computers and networks. When I moved to Rotterdam, there were no microprocessors; it would take another two years for that to happen. It would take six more years before Microsoft was formed.

There was only a rudimentary operating system, and we had to program it in assembly language. It was a significant challenge to develop the software. The biggest challenge was getting all the software into such a small memory. Every bit counted.

We created our programs sitting around a big table. First, we would write the instructions on paper. Then, when we got computer time, we could enter the program into the computer using a teletype. The programs would then be stored on a digital tape system. We would often show our programs to each other to see if any things needed to be corrected. Since we only had one computer we could program and there were about five programmers, we had to be very careful. There was a magnetic board that had the times for the computer. Each of us had a marker, and we could reserve time. After a while, I no longer programmed, which I still miss. Writing programs for me was like composing music. Starting with a blank piece of paper and a pencil, I could create something out of nothing.

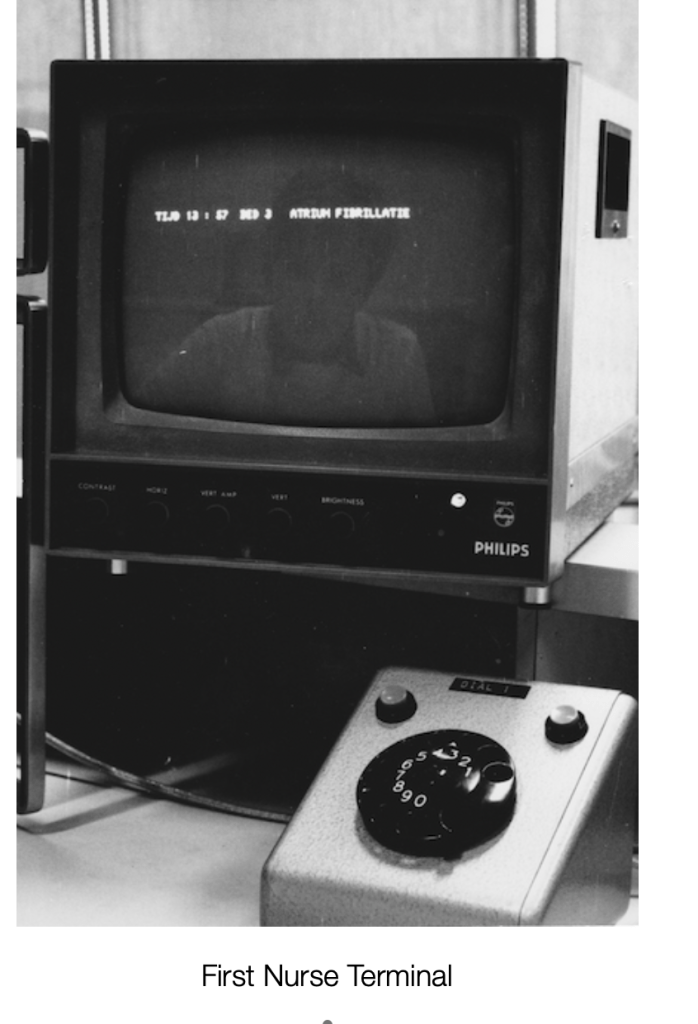

Display terminals

Display terminals did not exist in general. We used teletype to communicate with the computers, but that did would not work for the nurses in the ICU. So, we used a specialized video disk that could create characters that could be displayed on standard televisions.

We also had to create hardware. For instance, we had to build a console for nurses to access the information the computer system generated. At first, we had no idea how to let the nurses interact with the computer system. Then we decided to use a telephone dial. We had a list of functions, like menus, and a number following every function. The nurse would then dial in the number. A year or so later, we designed a nurse keyboard. I remember looking for keys and deciding the buttons used in elevators would be perfect.

We surveyed the nurses once the system was operational and asked about their favorite functions. I was horrified to learn that the function gave them the time digitally. I thought we had just built the world’s most expensive clock.

Catheterization Lab System

The most successful computer system we developed was for the Catheterization Lab. A cardiac catheterization lab is a specialized medical room for diagnosing and treating heart conditions. It uses advanced imaging to view heart arteries and chambers. We designed a specialized computer system using a PDP-11 from Digital Equipment Corp. We utilized a video disk system developed for instant replay of sports events to allow the cardiologist to replay the injection and flow of dye in the coronary arteries. Then, we figured out how to subtract the background so that the flow of the dye became more visible

The system we developed was instrumental in the development of many medical procedures.

Echo Cardiogram

The Thoraxcenter was a leader in using Echo Cardiograms. An engineer named Klaas Bom led this effort, and my group supported his computer requirements. Klaas played a significant role in developing the Thoraxcenter and eventually became head of biomedical engineering.

Computers in Cardiology Conference

Over the five years, I was at the Thoraxcenter, it gained international recognition as a leader in applying computer technology to cardiology. The Thoraxcenter was one of the founders of the Computers in Cardiology Conference. After leaving the Thoraxcenter in 1974, I attended this conference for several years and stayed in touch with people at the Thoraxcenter this way.

Leaving the Thoraxcenter

My family and I immigrated to Israel in 1974. There, I established a business based mainly on my work at the Thoraxcenter. I was also appointed as an Associate Professor in the Department of Cardiology at the University of Tel Aviv.

I transitioned from the medical world to the computer industry when I joined Digital Computer Corp in 1979 as the head of low-end computer engineering and later as the Group Manager for Professional Computers. I would go on to become a vice president at Intel, one of the world’s top companies. There, I co-founded Intel Capital.

Paul, my Mentor

Paul Hugenholtz had a distinguished career. He stayed as head of the Thoraxcenter until 1988. From 1982-1984, he served as President of the European Society of Cardiology. He was the founder of the Netherlands Heart Institute. He is still alive but at 97, not in good health.

But he was also one of the critical people that took a chance on me. He became my mentor and, most importantly, my friend. I owe him much. One of the joys of writing this blog post is thinking back to my time with Paul. He taught me the value of humor, the effectiveness of charm, and the importance of drive in achieving goals.

Here is a beautiful interview with Paul some eight years ago where he reflects on his life.

After working for Paul for five years, he made me an offer. The Medical Center wanted to create a significant outpatient clinic that would handle more than a million patients annually. Paul had been asked to develop a plan and recruit someone to lead it. While it would utilize computers, Paul wanted someone who could imagine how such a center could function. He wanted someone who would embrace the future. He turned to me and asked me if I would like this assignment. I was stunned. It was a significant project, much more vast than anything I had done. I was not a doctor and not even an engineer. But what really hit me was that Paul acknowledged that my Thoraxcenter task was done.

I thanked him and asked, “Am I done setting up the computer department at the Thoraxcenter?” He said yes that I had done all that had been expected of me and more. I thank him for that. Then I surprised myself and said, if I am done, I am going to leave the Netherlands and immigrate to Israel. This was something that Arianne and I had contemplated for a while. After what had happened in the war, we wanted to bring up our children in Israel. Paul did not try to dissuade me. He understood dreams better than most.

Avram, fascinating, as usual. Very kind to share this snapshot of what was “history in the making”‘. Thank you

LikeLike

IT HAS BEEN SUCH A … PURE JOY!!! >>> to READ your BLOG!

Thank you. For sharing your stories! MSJ@IIIMACRO.COM

LikeLike

What a wonderful yarn and now a “Dutchman” after all those years.

LikeLike